[ad_1]

By Stuart Mitchner

I sat me down to write a simple story which maybe in the end became a song…

—Keith Reid (1946-2023), from “Pilgrim’s Progress”

The first “simple story” Keith Reid gave to the world took some strange and wonderful turns. According to Beyond the Pale, Procol Harum’s rich, many-leveled website, “A Whiter Shade of Pale” sold more than 10 million copies worldwide, was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, and has inspired as many as a thousand known cover versions while becoming, says the BBC, “the most played song in the last 75 years in public places in the UK.”

The first “simple story” Keith Reid gave to the world took some strange and wonderful turns. According to Beyond the Pale, Procol Harum’s rich, many-leveled website, “A Whiter Shade of Pale” sold more than 10 million copies worldwide, was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, and has inspired as many as a thousand known cover versions while becoming, says the BBC, “the most played song in the last 75 years in public places in the UK.”

And it all began when Keith Reid mailed the lyrics to singer/pianist Gary Brooker in an envelope addressed simply “Gary, 15 Fairfield Road, Eastwood, Essex” and postmarked South Lambeth. You can see the very envelope on the website, along with a photo of the Burmese Brown cat for whom the group was named.

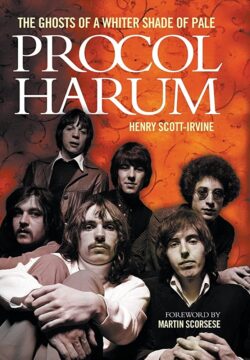

Introduced by Scorsese

The song that has fascinated generations since it was released in the UK as a single on May 12, 1967 is not by any means Reid’s most impressive accomplishment. In his foreword to Henry Scott-Irvine’s group biography Procol Harum: The Ghosts Of A Whiter Shade of Pale (Omnibus Press 2012), Martin Scorsese points out that the band “drew from so many deep wells – classical music, 19th Century literature, Rhythm and Blues, seaman’s logs, concertist poetry,” each tune becoming “a cross-cultural whirligig, a road trip through the pop subconscious.”

One of a Kind

If you take a world tour of Keith Reid’s lyrics, as I’ve been doing, it becomes clear that this unprepossessing fellow in the glasses who works offstage, never singing or performing on record or in person, is an incomparable writer of lyrics, or word-movies, that Gary Brooker turns into music with “a piano style steeped in gospel, classical music, blues and the British music hall,” for “songs that mixed pomp and whimsy, orchestral grandeur and rock drive,” according to the New York Times obituary for Brooker, who died on February 19, 2022, a little over a year before Reid’s death on March 23, 2023.

Crashing the Party

Writing about Haruki Marakami and the Beatles last week, I inserted Keith Reid into the mix as “the Murakami of Rock,” a shot from the hip meant to suggest the quality of the company Reid deserves. For an artist who is truly one of a kind, the real question is what company, who, where and when? After seeing Transatlantic, the recent Netflix series in which surrealist poet André Breton is among the writers and artists being helped out of Vichy France by the Emergency Rescue Committee, I’m imagining a bespectacled young Englishman at the party Breton organized at a villa outside Marseilles, where, after some coaxing and a few drinks, he’d be trying out lines like “your skin crawls up an octave, your teeth have lost their gleam” while “the mirror on reflection has climbed back upon the wall” as “the ceiling flew away.”

Reid and the Beatles

Around the time John Lennon and Paul McCartney made the word-movie “A Day in the Life,” Reid had already created “Salad Days,” “Homburg,” and numerous others like the ones I just quoted, including “A Whiter Shade of Pale,” which hit the top of the British singles charts the same week in 1967 that Sgt. Pepper topped the album charts. That said, Beatles lyrics seldom occupy a world as truly surreal as Reid’s. Even the most colorful, quotable lines in “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” belong to a more earthly planet of the imagination than the market square in “Homburg” where the town clock’s hands “turn backwards” and “on meeting will devour both themselves” and “any fool who dares to tell the time.” And as “Homburg” breathes its last (“the sun and moon will shatter and the signposts cease to sign”), singer Gary Brooker makes sure every word counts. Speaking of Brooker in his introduction to Scott-Irvine’s biography, film director Sir Alan Parker is “amazed as to why he isn’t seen as the greatest singer in the world. The guy could sing literally anything!” — including a lyric like “Christmas Camel,” which begins with “My Amazon six-triggered bride now searching for a place to hide….”

Thrilling Music

The first word of the eight-minute epic “Whaling Stories” on Procol Harum’s fourth and darkest album Home (1970) suggests a link to “Whiter Shade” in the composer’s mind: “Paling well after sixteen days, a mammoth task was set….” The rest of the stanza suggests that Keith Reid’s ship has already set sail on strange seas of thought: “Sack the town, and rob the tower, and steal the alphabet / Close the door and bar the gate, but keep the windows clean / God’s alive inside a movie! Watch the silver screen!”

By now Reid knows that his words will be sung with gusto and joyous authority, nothing overwrought, just more of the Brooker life force that prevails even when the doomsday trumpets are blowing. He delivers “God’s alive” with a full measure of glory, echoing “God’s aloft” from the preceding song, which continues the nautical theme Reid introduced in Procol’s acclaimed third LP A Salty Dog (1969).

That God’s alive in Reid’s movie is no surprise, given his lifelong interest in classic films like Pandora’s Box (the title of a great song in Procol’s Ninth) and The Sea Beast, an early silent version of Moby Dick starrring John Barrymore, remade as a talkie in 1930 with Barrymore hamming it up as Captain Ahab. Apparently scenes from the 1956 version of Melville’s novel along with clips from Marlon Brando’s Mutiny On the Bounty have been incorporated into the video accompanying the YouTube video of “Whaling Stories.”

Consider this assortment of flamboyant phrases — “Angels mumbled incantations; Darkness struck with molten fury, flashbulbs glorified the scene; Echo stormed its final scream.” Now give the words to Gary Brooker for one of his most enthalling performances, with drummer B.J. Wilson leading the tumultuous procession and lead guitarist Robin Trower outdoing himself with piercing rephrasings of “shrieking steam!” and Echo’s final scream, before the sublime hush that comes with dry land and “Daybreak washed with sands of gladness, rotting all it rotted clean / Windows peeped out on their neighbours, inside fireside bedsides gleam.”

“Pilgrim’s Progress”

In a 2010 interview with Dmitry M. Epstein, Reid said he’s never thought of his lyrics as poems: “I think of them as statements. Someone who wrote about me said that I have a poet’s heart. I’d like to think that’s true.” Asked if his lyric to “Pilgrim’s Progress” depicts “a songwriting process,” he replied that “it’s exactly depicting the process of writing that particular song.” As he has done in other interviews, he stressed the importance of going with his instincts: “I don’t think there are any rules when it comes to writing songs.”

“Pilgrim’s Progress,” which closes A Salty Dog, is subtly, feelingly sung by organist Matthew Fisher, who provides a suitably restrained accompaniment, at least compared to his magnificent performance (Hammond organ heaven) on “A Whiter Shade of Pale,” where he merges the Aria from Bach’s Orchestral Suite BWV 1068 with the chorale prelude BWV 645 that amplifies “the feeling of loss” Scorsese referred to when explaining his use of the song in his short film Life Lessons (“for me, it captured the sense of a relationship ending” when”there’s nothing you can do to stop it”).

The beauty of “Pilgrim’s Progress,” however, is the plaintive simplicity of the words, sung by a man in the shadows who “sat me down to write a simple story.” Along the way, he gathers up his fears to guide him, he’d thought “to go exploring,” set foot on the nearest road, then looked in vain for “the promised turning” but only saw how far he was from home.

Rounding back to the opening line, Reid looks behind him, aware of all the writers that came before, then lifts everything to another level by taking his place in their company: “The words have all been writ by one before me / We’re taking turns in trying to pass them on.” The idea that “we’re taking turns” is driven home when Brooker takes over from Fisher’s organ to pound out a coda the band joins in on, carried by Wilson’s inspired drumming to a triumphant wordless chorus that resonates with the spirit of Procol Harum.

“Shine On Brightly”

Keith Reid has a predilection for the word shining and Gary Brooker puts it over as the two carry on through to the last album of the 1970s, Procol’s Ninth in spite of losing organist Matthew Fisher’s peerless playing, so crucial to the first three albums; and Robin Trower’s lead guitar, which led to a stadium-filling solo career. Only drummer B.J. Wilson stayed with Reid and Brooker to the end. Wilson, who died in a coma in 1990, is remembered by Jimmy Page in The Ghosts Of A Whiter Shade of Pale: “There was nobody to touch him. He almost orchestrated with his drumming – with his uniqueness on the kit. There was nobody in the world that could drum like B.J. Wilson. And that’s simply it.”

Brooker regularly visited Wilson during the years-long coma. “I tried to wake him up. I played different things to him. I’d sing to him. We were working on new songs using a drum machine. I’d play him the tracks with the drum machine, hoping he would hear it and go, ‘What the bloody hell is going on? I’ve got to get over there.’”

———

Special thanks to the incredible website Beyond the Pale, where much of the quoted material originated, including the last anecdote about B.J. Wilson. Keith Reid’s words and Procol Harum’s music are instantly available on YouTube.

[ad_2]

Source_link