[ad_1]

By Stuart Mitchner

Music is only understood when one goes away singing it and only loved when one falls asleep with it in one’s head, and finds it still there on waking up the next morning.

—Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951)

You know how it is at dusk when the day has ended but it hasn’t? The ambiance of that time of day was all through everything we played.

—Richard Davis (1930-2023) on recording Astral Weeks

I’m driving Mr. Schoenberg around Princeton on his 149th birthday, it’s a fine September day, everything’s clear and bright, and we’re listening to Pierre lunaire, the atonal 21-song “melodrama” Mr. S. composed in 1912 and conducted in Berlin that October.

I’m driving Mr. Schoenberg around Princeton on his 149th birthday, it’s a fine September day, everything’s clear and bright, and we’re listening to Pierre lunaire, the atonal 21-song “melodrama” Mr. S. composed in 1912 and conducted in Berlin that October.

“Poor brave Albertine,” Mr. S. says, referring to the soprano Albertine Zehme, the vocalist/narrator at the Berlin premiere. “The real melodrama was in the audience. She had to contend with whistling, booing, laughter, and unaussprechlich insults, but the loudest voice in that crowd was the one shouting ‘Shoot him! Shoot him!’ Meaning me.”

To those who say there’s no way I could be conversing with an Austrian-American composer who died on Friday the 13th, July 1951, I’ll quote my passenger, who in 1909 announced his “complete liberation from form and symbols, cohesion and logic” because it’s “impossible to feel only one emotion. Man has many feelings, thousands at a time, each going its own way — this multicoloured, polymorphic, illogical nature of our feelings, and their associations, a rush of blood, reactions in our senses, in our nerves” is all “in my music… an expression of feeling, full of unconscious connections.”

Composing in Motion

“I spent the last 18 years of my earthly life in Los Angeles and never drove a car,” says Mr. S. as we’re driving along Lake Carnegie. “My wife Trudy did all the driving. But I was happy being a passenger in the LaSalle, a good place for writing and sketching. Always a tablet in my lap. I scored bumps in the road, traffic, sketched green lights, red lights, giant hot dog signs — it was all free-flowing 12-tone to me, you know, painting sights and sounds. Now here I am riding in a car listening to my Pierrot in the numerically unthinkable year 2023, where anything, as you say, goes.”

Driving Mr. S. is a joy, or, as he would say, using his favorite Americanism of the moment, “Thumbs up!” He always gives you the gesture and the phrase, suits the word to the action, as I can see from the corner of my eye as we turn left on Prospect Avenue. Mr, S.’s setting of “Homeward Bound,” the 20th of Albert Grimaud’s 21 “Moonstruck Pierrot” poems, has been playing, matching lakeside to lyric (“The stream hums deep cadence and rocks the little skiff”), except the rudder is a moonbeam and the boat is a water lily.

“Driven into Paradise”

It’s not easy finding a photo of Schoenberg smiling or at least looking less like the Dr. Mabuse of music, as he does in Man Ray’s 1927 photograph. But who’s smiling when audiences in Vienna and Berlin have been noisily hostile to your “degenerate” work both before and after the 12-tone innovations (“Shoot him!”), and 20 years before the Nazis banned your music?

When Schoenberg arrived in Hollywood in 1934, he had plenty to smile about. The Third Reich had driven him into “Paradise,” California was “Switzerland, the Riviera, the Wienerwald,” and he was befriended by George Gershwin, who had studied and admired his work. It’s actually thanks to Gershwin that we have Edward Weston’s photograph of Schoenberg’s wry smile, as well as glimpses of the relaxed, amused, bow-tied composer being hugged and applauded in a home movie Gershwin made using Schoenberg’s String Quartet No. 4 for a soundtrack (the film can be seen on slippedisc.com).

Tennis and Music

The Schoenberg-Gershwin friendship developed during numerous games of tennis played on the court at Gershwin’s Beverly Hills villa. According to Kenneth H. Marcus in Schoenberg and Hollywood Modernism (Cambridge University Press 2015), Schoenberg had invented his own notation form to catalogue the moves he made on the court. One witness observed that Gershwin expressed “linear counterpoint in his strokes, while Schoenberg “concentrated on mere harmony, the safe return of the ball.”

The friendship was cut short by Gershwin’s sudden death from a brain tumor in the summer of 1937. At the time he had been working on a portrait of Schoenberg based on Weston’s photograph. In the tribute Schoenberg recorded, which was later added at the end of the home movie, he expresses his grief “for the deplorable loss to music,” and then says in his gently accented English, “May I mention that I lose also a friend whose amiable personality was very dear to me.”

“Astral Weeks”

When I was hypothetically driving Mr. S., he asked me to single out a recording from “the music you know best” that I valued above all others, one that lived up to his idea that music “is only understood when one goes away singing it and only loved when one falls asleep with it in one’s head, and finds it still there on waking up the next morning.” My answer was Astral Weeks. In fact, I’d already been listening to Van Morrison’s masterpiece because of elements it has in common with Pierrot Lunaire and most particularly because the musician rightly known as the “soul” of the record, bassist Richard Davis, died September 6 at the age of 93.

When I was hypothetically driving Mr. S., he asked me to single out a recording from “the music you know best” that I valued above all others, one that lived up to his idea that music “is only understood when one goes away singing it and only loved when one falls asleep with it in one’s head, and finds it still there on waking up the next morning.” My answer was Astral Weeks. In fact, I’d already been listening to Van Morrison’s masterpiece because of elements it has in common with Pierrot Lunaire and most particularly because the musician rightly known as the “soul” of the record, bassist Richard Davis, died September 6 at the age of 93.

According to Martin Johnson’s obituary on wrti.org, when Davis was growing up on Chicago’s South Side, his high school music teacher made sure that he studied both jazz and classical styles. Over a 70-year career, Davis played with Sarah Vaughan and Eric Dolphy, and with orchestras led by Leonard Bernstein and Igor Stravinsky, who called Davis “his favorite bassist.” It’s stunning to think that the same Stravinsky who lived long enough (1882-1971) to admire and employ Richard Davis was present in October 1912 at the fourth Berlin performance of Pierrot, which he says was attended by a “quiet and attentive audience,” in contrast to the turbulent premiere described by Mr. S. Quoted at length in Harvey Sach’s Why Schoenberg Matters, Stravinsky found that the soprano’s recitation got between him and “the real wealth of Pierrot, sound and substance,” which makes it “the solar plexus as well as the mind of early twentieth-century music, which was beyond me as it was beyond all of us at that time.”

In the Slipstream

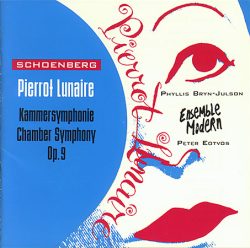

After driving to Kingston and back listening to the Pierrot Lunaire CD recorded in December 1991 by the Ensemble Modern, with sung-spoken narration by North Dakota native Phyllis Bryn-Julson, I drove to a neighborhood we once lived in, parked on Walnut Lane opposite the high school, and listened to Astral Weeks, music I’ve been loving and living with for half a century, compared to which Pierrot is alien territory. But the instant the sound of Richard Davis’s propulsive double bass fills the car, the boundaries of time and space and genre disappear as his undaunted bass-line creates the “unconscious connection,” and 1912-1968-2023 all flow into one “multicoloured, polymorphic” stream of feeling.

Conjuring

“If you listen to the album, every tune is led by Richard and everybody followed Richard and Van’s voice,” says Astral Week’s producer Lewis Merenstein. As the headline in the Rolling Stone obit put it, Davis “conjured” Astral Weeks.

In the album’s richest moments, multiple themes and tempos come into play at the same time. You’ve got Morrison strumming strong and steady on his acoustic guitar while singing passionate lyrical incantations that follow their own weird, sometimes staggered, sometimes staggering course (he calls his version of Schoenberg’s speech-melody “the inarticulate music of the heart”); you’ve got a mystery violinist weaving exotic subplots while the Modern Jazz Quartet’s drummer Connie Kay is telling his own story as the leaves on Cyprus Avenue “fall one by one by one” and Jay Berliner’s guitar puts another storyline into the mix; then there’s John Payne’s flute evoking “gardens all wet with rain,” and in the song-movie “Cyprus Avenue” there’s the tolling effect at the end in the form of a string arrangement so maddeningly evocative and haunting, it’s enough to send me to Van Morrison’s Belfast to see “the avenue of trees” for myself. Meanwhile driving under and over it all, Davis is creating hypnotic counterpoint to Morrison’s incantations.

In When That Rough God Goes Riding: Listening to Van Morrison (Public Affairs 2010), Greil Marcus asks, “What does it say, where did it come from?” as he ponders the “inexplicable” greatness of Astral Weeks. His answer, as good as any, is that this music tells both musicians and people who aren’t musicians “there’s more to life than you thought. Life can be lived more deeply with a greater sense of fear and horror and desire than you ever imagined.”

A Timeless Touch

Stravinsky outlived Schoenberg by 20 years, dying in 1971, which would have given him time to hear Astral Weeks, which was released in the fall of 1968. In a 2014 interview for the National Endowment for the Arts at arts.gov, Davis describes how it felt to play in an orchestra conducted by Stravinsky: “When he conducted it was so rhythmic and it was like his baton was just a part of his body. And I just loved being in his company. And that last concert [a performance of Rite of Spring] he had to exit off my side of the stage. He didn’t say nothing, just walked over to me and just…. You see this shoulder here? That’s where he touched me. Man. I’ll never wash that shoulder again. Haven’t washed that shoulder in 60 years.”

[ad_2]

Source_link