[ad_1]

By Stuart Mitchner

I have come to regard this matter of Fame as the most transparent of all vanities…

—Herman Melville (1819-1891)

In the same circa-June-1851 letter to Nathaniel Hawthorne, Melville made some of his best-known pronouncements about the illusory nature of celebrity. On the verge of completing Moby-Dick (“In a week or so, I go to New York, to bury myself in a third-story room, and work and slave on my ‘Whale’ while it is driving through the press”), he declared, “What’s the use of elaborating what, in its very essence, is so short-lived as a modern book? Though I wrote the Gospels in this century, I should die in the gutter.”

Melville came to mind as I was reading Celebrity Nation: How America Evolved Into a Culture of Fans and Followers (Beacon Press $26.95) by Princeton resident and former People magazine editor Landon Jones. A St. Louis native and fellow Cardinals fan, Jones drew my attention to Chapter 6, “How Celebrities Hijacked Heroes,” which ends with a page on the great Cardinal slugger Stan Musial (1920-2013). As Jones puts it, “Musial was our Galahad, our Achilles, our Hector — a modest, decent soft-spoken man who did more than anyone to raise St. Louis to its reputation as a good sports town where the fans even clap for the opposing team’s players.”

Baseball and Celebrity

Jones uses Musial to develop his point about the way “the overabundant cheap coins of celebrity have driven the limited supply of the truly heroic out of circulation.” Recalling the one time he had a chance to ask Musial a question in person, he admits he “blew it” by bringing up a decisive play in the 1946 World Series when he could have been talking about Jackie Robinson and the integration of baseball. Jones concludes that “celebrities are more likely to reinforce our preconceptions than to lead us to new ideas. Consequently the culture feels recycled, mired in the same nostalgia I felt when I met Musial.”

The only time I saw Musial at close range was on the courthouse square in Bloomington, Indiana, in October 1960. He was campaigning for John F. Kennedy with a group of celebrities — movie stars Jeff Chandler and Angie Dickinson and author James Michener — who were being subjected to boos and catcalls from a crowd dominated by “Young Republicans” from Indiana University. When Musial took the stage, the crowd saw Galahad, Achilles, Hector, and the soft-spoken nice guy all in one living absolute that middle America knew as Stan the Man and suddenly the jeers turned to cheers.

More Than a Celebrity

The same week that I’ve been reading about the culture of celebrity, the death of Irish singer-songwriter Sinéad O’Connor turned the notion on its head, or, you could say, ripped it to pieces, since the media has been obsessively rerunning the moment in 1992 when she tore up a photograph of the Pope on national television. “A Lonely Voice for Change, Until Her Country Changed With Her” is one of several headlines on the full page of coverage the New York Times devoted to her two days after breaking the news. For the “newspaper of record” O’Connor is more than a celebrity, she’s newsworthy on the grand scale, in her own heroic right, her stature based on the raw courage it took to risk infamy and the alienation of “fans and followers” by standing up for her beliefs.

Nothing Compares to Her

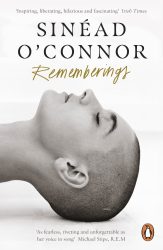

Channel-surfing one night in 1990 I found myself eye to eye with a stranger who was singing, softly at first, a song I’d never heard before in a voice as intimate as a kiss, so close I could feel the breath of every word. At the end when the screen identified Sinéad O’Connor and the song, “Nothing Compares 2 U,” it was as if MTV read my mind. Prince may have composed the song, but it’s incomparably hers — she’s lived every word, every nuance, every cry from the heart. Watching the video again and hearing the piercing purity of her voice a day after her death at the age of 56, I thought of the passage in her 2021 memoir Rememberings, where after learning she’d been nominated for her first Grammy, she saw her life “roll up as if it were a blanket and vanish. Quick as a flash, like I was a dying person.” As if success were a death sentence. She refused to attend the ceremony.

Princess Di

According to Landon Jones, who headed People during its prime, “It is still hard to assess the celebrity apotheosis that Diana represented in 1994…. Unwillingly or not, she was as much a part of the celebrity-industrial complex as Elizabeth Taylor.” Reporting on a 1994 visit with Diana, the subject of a record 58 People covers, Jones provides some poignant glimpses: “She had a beguiling habit of clapping her hands on her face or crossing them on her chest if something amused her or if she were laughing at herself.” Jones closes the chapter with his “lasting image of the Princess of Wales standing by her doorway, alone, plaintively waving goodbye.”

Prince Harry’s Face

Try ignoring the face on the cover of Prince Harry’s memoir Spare (Random House $36). Can’t be done. There’s a strong hint of “if looks could kill” in the intensity of his gaze that almost makes you feel like an investor in the paparazzi-infested machinery of celebrity that destroyed his mother. Go face to face with Sinéad O’Connor in that haunting video and you’re hers, you’re in her song, in her eyes, in her story. You don’t want to get too close to the neatly groomed Viking warrior on the cover of Spare.

When the book begins, Harry has arrived in the U.K. for Prince Philip’s funeral, he’s in the Frogmore Gardens waiting for the other Royals to show up. A “gust of wind” reminds him of Grandpa’s “icy sense of humor” and of the time years ago when a friend of Harry’s asked Philip what he thought of “my new beard, which had been causing concern in the family and controversy in the press. Should the Queen Force Prince Harry To Shave? Grandpa looked at my mate, looked at my chin, broke into a devilish grin. THAT’S no beard!” — at which Viking Harry’s thinking, “leave it to Grandpa to demand more beard. Let grow the luxurious bristles of a bloody Viking!”

In the next paragraph, Harry remembers that Prince Philip was Diana Spencer’s loudest advocate. “Some said he actually brokered my parents’ marriage. If so, an argument could be made that Grandpa was the Prime Cause in my world. But for him, I wouldn’t be here.” On a separate line he adds, “Neither would my older brother.” And on another line under that: “Then again, maybe our mother would be here. If she hadn’t married Pa.” Harry, or his ghostwriter, uses the same structural emphasis to put a charge into Harry’s loathing of the press. At his mother’s funeral, age 12, he hears “a rhythmic clicking from across the road. The press. I reached for my father’s hand, then cursed myself, because that gesture set off an explosion of clicks.” On a separate line: “I’d given them exactly what they wanted. Emotion, Drama. Pain.” Next line down: “They fired and fired and fired.”

Heroes for Sale

The game my baseball-crazy, sub-teen self played on a board with a spinning arrow is alive and well in 2023 as Fantasy Baseball. My game had round cards for each player, and what a group. You could field a team mixing Babe Ruth and Ted Williams, Ty Cobb and Stan Musial, the one player who was always on my team, just as he remained a St. Louis Cardinal for his entire 22 year career. During the last week of July, with the trade deadline looming, today’s owners play their own billion dollar version of Fantasy Baseball, and in the baseball universe everyone’s talking about the celebrity players who might be sold or traded by fading teams to teams with a shot at the playoffs. The big names that create headlines on ESPN and elsewhere have a certain celebrity status, but the idea of the “hero” has ceased to mean much and no wonder when heroes are bought and sold, further evidence of Jones’s claim that “cheap coins of celebrity” have driven “the truly heroic out of circulation.”

Melville’s Harbor

Tuesday having been Herman Melville’s birthday, I’ve just paid a YouTube visit to Sinéad O’Connor’s video rendition of “Harbor,” a stirring song by Melville’s great-great-great-grandnephew Richard Melville Hall, best known as Moby. I strongly recommend watching and hearing the video. Written sometime before or after September 11, 2001, the song appears on Moby’s LP 18, and conveys a sense of a haunted Manhattan (“I run the stairs away / And walk into the night-time”) that can be found in some of his great-uncle’s stories and poems and the novel Pierre, written in the aftermath of Moby-Dick. Both novels gave credence to Melville’s thoughts on fame and the short life of “a modern book.” Two decades into the 20th century the so-called Melville Revival was underway, with Moby-Dick soon to be celebrated as one of the great, if not the greatest, American novel.

[ad_2]

Source_link