[ad_1]

By Stuart Mitchner

I was born in the spring of 1941. The Second World War was already raging in Europe, and America would soon be in it.

—Bob Dylan, from Chronicles

Bob Dylan will turn 82 today (Wednesday, May 24, 2023). This week I’ve been listening to tenor saxophonist Dexter Gordon, who was born 100 years ago February 27, and singer songwriter Gordon Lightfoot, who died at 84 on May 1. Incidental music is provided by John Donne (1571/2-1631).

Bob Dylan will turn 82 today (Wednesday, May 24, 2023). This week I’ve been listening to tenor saxophonist Dexter Gordon, who was born 100 years ago February 27, and singer songwriter Gordon Lightfoot, who died at 84 on May 1. Incidental music is provided by John Donne (1571/2-1631).

A Tortured Torch Song

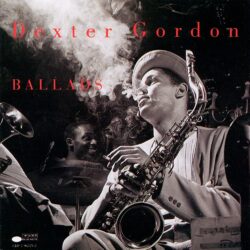

Released a year after his death in 1990, Dexter Gordon’s Blue Note album Ballads features standards like “Willow Weep for Me” and “Darn That Dream.” The track that I’ve been fixated on, however, is the relatively little known “I Guess I’ll Hang My Tears Out to Dry,” a tortured torch song with lyrics by Sammy Cahn and music by Jule Styne. Composed for Glad To See You, a musical that folded before reaching Broadway, the tune dates from 1944, when America was three years into the war.

Although I’ve been listening to “Tears” on my copy of Gordon’s 1962 Blue Note album Go, the cover of Ballads is shown here because of Herman Leonard’s justly famous photograph, taken in 1948 when Dexter was 25. Much to my surprise, I found that this seemingly obscure song has been recorded by at least 25 artists, including Frank Sinatra, who sings the line “When I want rain, I get sunny weather” with almost operatic bravura. A big man with a big sound, Gordon produces a work of searing, cry-in-the-night intensity, blowing through the passages that singers have to deal with (“Dry little tear drops, my little tear drops hanging on a stream of dreams”). Still, it’s obvious that Gordon knows and feels the words. The power of his playing makes something strange and wonderful out of this piece of musical comedy make-believe. According to the Dexter Gordon chapter of Gary Giddins and Scott DeVaux’s invaluable book Jazz (W.W. Norton 2009), “Before performing a ballad, he would often quote the tune’s lyrics, as if inviting his listeners to take part in the deeper world of the song.”

Donne and Disney

Think too long about tears hung out to dry and you begin seeing a surreal cartoon of Mickey Mouse hanging his teardrops on a clothesline after a spat with Minnie. And if you’re a lifetime graduate student of English literature pondering the way tunesmiths play fast and loose with reality in Tin Pan Alley’s land of hopes and dreams, you soon find yourself thinking of John Donne, who would have no problem understanding the notion of tears as metaphorical entities drying on backyard clotheslines in wartime and postwar America. Donne covers the perceptual issue in “Go and Catch a Falling Star” (“If thou be’st born to strange sights, things invisible to see”), and “The Dreame” (“When you are gone, and Reason gone with you. / Then Fantasie is Queene and Soule” and “all our joys are but fantasticall”).

Never Too Late

The people in Gordon Lightfoot’s song “Rainy Day People” don’t mind “if you’re crying a tear or two” when “you get lonely.” They know there’s “no sorrow they can’t rise above,” including, I think, the sorrow of only discovering the music after the musician dies. I never bought Lightfoot’s records and in 2023 there’s not a single CD of his at the library, but in the limitless library of YouTube, you can hear him singing the timeless line “What a tale my thoughts could tell.”

In a 2011 interview, Dylan ranked Lightfoot near the top of his list of “favorite songwriters.” Quoted in a post on faroutmagazine.co.uk after Lightfoot’s death, Dylan says “Every time I hear a song of his, it’s like I wish it would last forever…”

“If You Could Read My Mind” is a “forever” song, one that’s been waiting to be written since the time of, yes, John Donne, who could connect with a lyric wherein the singer becomes “a ghost from a wishing well” with chains upon his feet, who will “never be set free” as long as “he can’t be seen by his love.” In “Shadows,” a Lightfoot song that Dylan sings in the faroutmagazine post, the singer dreams that “when the morning stars grow dim, they will find us in the shadows fast asleep.” In the line that resonates throughout the song, the singer becomes a “shadow” at his lover’s door.

Dylan Dreams a Song

Dylan knows about stars and shadows. “A song is like a dream,” he says in Chronicles, where he describes how it happens: “From the far end of the kitchen a silver beam of moonlight pierced through the leaded panes of the window illuminating the table. The song seemed to hit the wall, and I stopped writing and swayed backwards in the chair.” Even in a passage about the cyclical, numerical approach to songwriting, Dylan stresses the song as an experience, where you “know why the number 3 is more metaphysically powerful than the number 2.”

DJ Dylan’s Tears

Tears are another facet of musical life that Dylan covered in his Theme Time Radio Hour on Sirius XM between 2006 and 2009 (and occasionally thereafter, even as recently as 2020). The broadcast devoted to the subject is referenced online in Dr. Jeff Rubin’s “From Insults to Respect.” After beginning the show with “96 Tears” by Question Mark and the Mysterians, Dylan delivers a Dylanesque DJ intro: “We’re gonna learn about sad clowns, crocodiles, and tear-stained makeup. We’re gonna look at a river of tears as we learn about crying, so grab yourself some Kleenex.” You’re more likely to smile than weep when he comments on Anita O’Day’s “And Her Tears Flowed Like Wine”: “She’s a real sad tomato. She’s a busted valentine.” Sad to say, but nothing to cry about, Dylan doesn’t comment on Cahn and Styne’s tortured torch song. Nor on “Tears of Rage,” which he wrote with the The Band’s Richard Manuel.

The Dream Duo

Herman Leonard’s photograph of Dexter Gordon suggests a smoke-hazed world of stories from the life of a musician who triumphantly survived the curse of drugs that took down his good friend and fellow tenorman Wardell Gray. When L.A.-based Dial Records brought out the Dexter-Wardell Central Avenue jams on a series of 78 rpm singles, “The Chase” and “The Hunt” were among the best-selling jazz recordings of the post-war era. They were also fervently listened to by Jack Kerouac and Neal Cassady. “We’d stay up 24 hours,” Kerouac writes, “drinking cup after cup of black coffee, playing record after record of Wardell Gray, Lester Young, Dexter Gordon … talking madly about that holy new feeling out there in the streets.” In The Unknown Kerouac (Library of America $35), jazz is “the actual inner sound of a country.”

For Kerouac’s friend John Clellon Holmes, “The Hunt” was “the anthem in which we jettisoned the intellectual Dixieland of atheism, rationalism, liberalism — and found our group’s rebel streak at last.” Kerouac himself gets right to the excitement in On the Road, with Neal (Dean Moriarty) and Jack (Sal Paradise) “bowed and jumping before the big phonograph, listening to a wild bop record called ‘The Hunt,’ with Dexter Gordon and Wardell Gray blowing their tops before a screaming audience that gave the record fantastic frenzied volume.” Another passage has Dean and Sal playing catch to “the wild sounds” of ‘The Hunt.’ ”

I mention the postwar nationwide excitement the two tenors created as a preface to a fantasy of mine straight out of Donne’s “The Dreame,” while knowing that my dream, like “all our joys” is “fantasticall.” But supposing that beyond the snares of drugs and death, Gordon and Gray formed a group in L.A. and brought it to New York when On the Road was introducing thousands of listeners to their music. In addition to recordings of “The Hunt” and “The Chase” you can hear the commercial possibilities of the two-tenor sound on Citizens Bop, a 1997 CD, where the combination of force, wit, and energy comes through in the title track, two takes of “The Rubiyat,” and a Christmas number, “Jingle Jangle Jump.” At the time my smoke dream duo might have made a splash, roughly 1957-1959, Wardell had been dead since May 1955 and Gordon in and out of prison for drug possession.

Dylan Quotes Wilson

The last person quoted in Dylan’s broadcast on tears is former president Woodrow Wilson: “There is little for the great part of history except the bitter tears of pity and the hot tears of wrath.” Also quoted on Rubin’s “From Insults to Respect” site (if not in the broadcast itself) is a statement by Wilson dated 1919: “I am a most unhappy man. I have unwittingly ruined my country. A great industrial nation is now controlled by its system of credit. We are no longer a government of free opinion. No longer a government by conviction and the vote of the majority, but a government by the opinion and duress of a small group of dominant men.”

Wilson’s statement has been widely discussed and disputed in a Wikipedia Talk on the Federal Reserve Act. Apparently, the statement has been patched together with phrases that can probably be attributed to Wilson. The possibilities, let alone the gist of Wilson’s statement, don’t seem at all dated in May 2023.

[ad_2]

Source_link