[ad_1]

Earlier this month, after the high energy NJ AFL-CIO nurses’ rally for safer staffing, I had time on my hands to explore the areas of the New Jersey State Capitol Building that have been off limits to inquiring reporters and the public due to the $300 million renovation that got rolling at the end of Gov. Christie’s traumatic tenure.

Going back to the McGreevey days there was one stairway out of the subsurface floors and the parking garage that was to the left of the vending machines that I used to get quick access to the Governor’s Office and the historic Rotunda where all of New Jersey’s Great White Men hang in oil.

For a while now, like years, it’s been walled off but on this glorious day in May it was restored, and access was once again possible.

A uniformed guard sat some distance away behind a desk in the basement and I asked him if it was o.k. to use the handy staircase that would take me to the very heart of the Executive Branch. He seemed confused because it was apparently something he hadn’t been asked before. He asked a colleague, and the pair didn’t stop me.

The convenience of that stairs for reporters can’t be overstated. Not only did it provide you the most direct route to the Governor’s ceremonial office on the first floor, but it also got you on the staircase up to State House Press row where all of the newspapers had their offices directly across from the Governor’s press offices on the upper floor.

Perhaps I could catch up with some newspaper colleagues I thought. I could bust their chops for not attending the nurses’ rally. I could discern which newspapers had made it into the 2020s with a presence in the State House keeping an eye on our “cold blooded capitalist” of a Governor.

As I ascended the stairs to the first floor, my nostrils were overwhelmed with the smell of fresh paint and wood finishings. The erudite voice of a polished tour guide back at work filled the restored Rotunda with a velvet whisper.

I took time to appreciate each of the Rotunda’s portraits of past New Jersey Governors for whom the state’s highest office had either been a sort of consolation prize or a stepping stone to higher office.

There was Gov. George B. McClellan, who was elected in 1878 but is perhaps better known as the General McClellan who in September of 1862 led the Union Army to victory at Antietam, the bloodiest battle of the Civil War.

According to battlefields.org, McClellan, was a West Point graduate and civil engineer who was a charismatic figure for the rank and file soldiers that made up the Union Army. Despite his success at repelling the Confederate Army’s northward advance, President Lincoln felt he had squandered the pivotal win and sent his packing to Trenton.

“Though he had managed to thwart Lee’s plan to invade the North, McClellan’s trademark caution once again denied the northern cause a decisive victory, and the once-cordial relationship between the army commander and his Commander-in-Chief had been badly damaged by the former’s lack of success and excessive trepidation,” the battlefields.org website recounts. “After the battle, a disappointed Lincoln visited McClellan in camp to express his frustration at the general’s inability to capitalize on this most recent success…. McClellan was relieved of command for the last time and ordered back to Trenton, New Jersey to await further orders, though none ever came.”

In 1864, McClellan ran as a Democrat challenging Lincoln’s re-election on an anti-war platform, pledging to pursue peace talks with the Confederacy but by Election Day the Union Army had victory in their sights and Lincoln was re-elected. However, McClellan did carry the State of New Jersey by five percentage points.

Less than a year later, Lincoln would be assassinated. As I have written before, New Jersey was at best ambivalent about the institution of slavery and had been very much reliant on it. Just before the end of the Civil War, New Jersey even voted down the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery, only voting to ratify it in 1866, after the end of the Civil War and after Lincoln’s murder.

McClellan would be elected Governor in 1878.

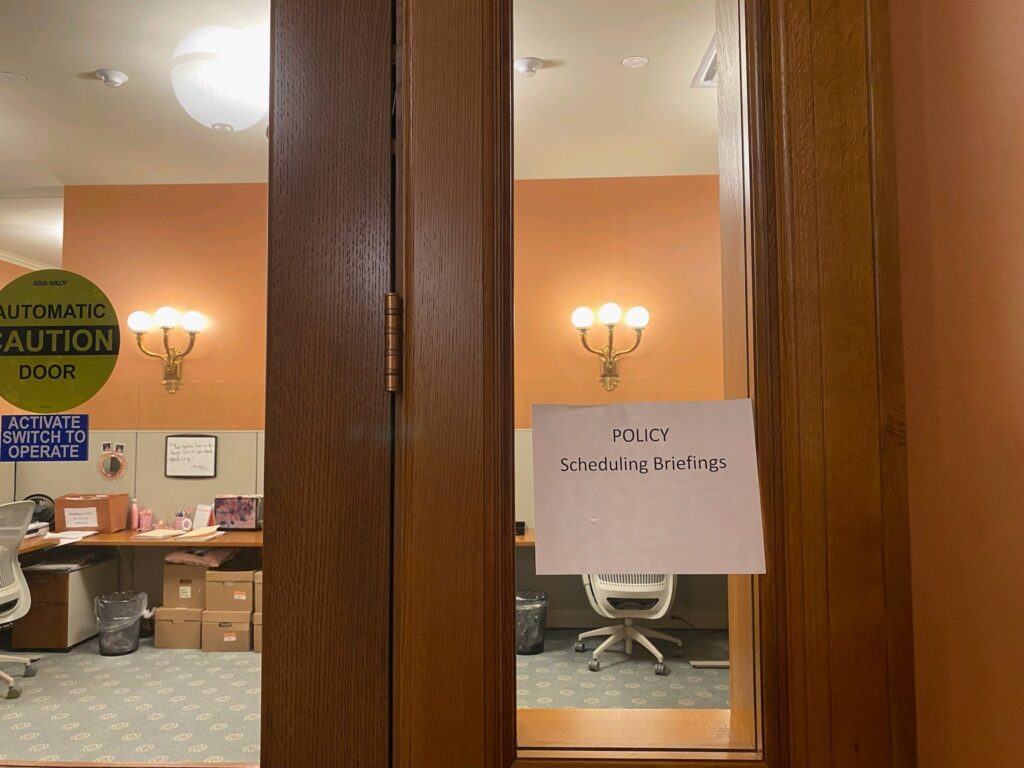

I circled back to the staircase after my quick promenade down history lane and jogged upstairs to where Press Row had been located and saw that the entire floor had been reconfigured with all of the space that had accommodated New Jersey news media outlets subsumed by what appeared to be more offices for the Executive Branch.

The only clue was a sign on the door “POLICY Scheduling Briefings.” What had happened to press row? Someone who appeared to be a staffer came out of what had been previously the Governor’s press office and was headed back down to the first floor. I asked her where all the reporters’ offices had moved to and she said she would find out.

When we both headed back down to the first floor I asked the New Jersey State Trooper on duty outside Governor Murphy’s office where I could find Press Row as the staffer made her own inquiry for me in the front office.

There was a nicely upholstered bench and I asked if I was allowed to sit on it, figuring it could be some antique meant just for viewing. The Trooper said I could. While I waited I thought about the portrait of Gov. Woodrow Wilson, another Democrat who had presidential ambitions that resulted in two terms in the White House from 1913 to 1921.

Wilson was considered a progressive reformer perhaps best known for his unsuccessful bid to establish the League of Nations, a forerunner of the United Nations. On his watch the U.S. enacted the Federal income tax, established the Federal Reserve as well as the Federal Trade Commission to crack down on widespread deceptive business practices.

On the labor front, he championed passage of anti-child labor laws and workplace safety protections for rail workers by limited their workday to eight hours.

But as it turns out, decades after the Civil War, it was our very own Woodrow Wilson, the president of Princeton University, Governor of New Jersey, and the 28th president of the United States, who propagated the view that North’s Reconstruction was a great injustice that victimized whites, that Wilson believed were inherently superior.

Despite is Princeton pedigree, Wilson, a native of Virginia, was the first president who was a son of the South since the Civil War. His father was a chaplain for the Confederate Army. Long before he entered the fray of electoral politics, his academic writing was very influential in creating a racist revisionist history that became mainstream.

“The first practical result of reconstruction under the acts of 1867 was the disfranchisement, for several weary years, of the better whites, and the consent giving over of the southern governments into the hands of the negroes,” Woodrow Wilson wrote in the Atlantic.

The man, whose name is memorialized in stone at the Wilson Center, the prestigious international think tank located in Princeton, wrote former slaves were “a vast laboring, landless, homeless class…..unpracticed in liberty, unschooled in self-control; never sobered by the discipline of self-support, never established in any habit of prudence; excited by a freedom they did not understand, exalted by false hopes; bewildered and without leaders, and yet insolent and aggressive; sick of work, covetous of pleasure, — a host of dusky children untimely put out of school.”

One of Wilson’s earliest acts as president was to sign off on racially segregating the federal civil service.

“By the end of 1913, Black employees in several federal departments had been relegated to separate or screened-off work areas and segregated lavatories and lunchrooms,” according to the Equal Justice Initiative. “In addition to physical separation from white workers, Black employees were appointed to menial positions or reassigned to divisions slated for elimination. The government also began requiring photographs on civil service applications, to better enable racial screening.”

Wilson’s early 20th century racist beliefs would find 21st century arms and legs with Donald Trump’s race-based grievance of whites as victims which fueled the racist mob that stormed Congress on Jan. 6, 2021. On that day, the Confederate Stars and Bars Battle flag lead the charge into the federal Capitol Rotunda, something that McClellan had prevented from happening during the Civil War.

It was Wilson who actively suppressed word of the so-called Spanish Flu in 1918-20, because it would have hampered the U.S. World War I effort. At least 675,000 people died in the United States and 50 million around the worldwide. More American soldiers died from the Spanish Flu then were killed in combat.

The global scourge would be forever named for Spain, not because it was the point of origin of the killer virus, but because word of it surfaced in the press there —as Spain did not have the effective wartime press censorship we had here.

The Murphy staffer came back out and told me press row had been moved to a floor above where it had been. The Trooper said I could take the elevator.

Up on that floor there was one room of cubicles for interns, and another similarly appointed space for reporters which on this day there was only one of on duty, Charlie Stile, the veteran political columnist for the Record, aka northjersey.com.

Stile has been covering New Jersey politics from the Statehouse in Trenton since 1993, starting with the Trenton Times. He worked as a general assignment reporter for the Record and Statehouse bureau chief before becoming its full-time columnist in 2007.

Having spent big chunks of my life in what had been press row offices for WNYC I was stunned by the downsizing. Where was everybody? I asked Stile what he thought.

“It’s unfortunately small,” Stile said. “It’s clean. It’s got a nice view, but it lacks privacy but sadly it does reflect the reality of current journalism. We are just not that big a presence. When I first came here there were 12 bureaus each having their own private office in a warren of offices on the second floor ranging from the New York Times which had two people to the Star Ledger which had about 12.”

Stile continued. “I came here with the Trenton Times and there were four of us and the Record had about six or seven. It was a time of high energy—a bustling nerve center, and it was right across the hall from the Governor and there was easy but tense access to the Governor’s office.

You could find them in the hallways by the vending machine, sometimes even in the bathrooms for interviews.”

“Proximity mattered— I think it broke down some of this veil of suspicion and skepticism. But without that kind of day-to-day interaction, it can boil into something more pernicious,” Stile said.

I asked him if he thought that the ability of the Governor to use social media to leapfrog the fourth estate, a practice perfected by Gov. Christie, had played a role in diminishing the state house press corps.

“Absolutely—they bypass the traditional gatekeepers and there’s the sad reality and acknowledgement that the gatekeepers are not this formidable force that they once were,” Stile said. “In their minds, their mission is to go where the voters are and I think they see that as the easiest way number one, and number two—its an unfiltered way. They don’t have to be pestered with impertinent questions or perspectives. They can speak to the public solely on their terms.”

But the lost clout of journalism is not all that Stile misses.

“What I do miss was the sharing of ideas—talking with each other. Picking up ledes and the ability to spitball ideas with colleagues from rival papers. It was an amazing and necessary dynamic and I think these bright, super talented kids coming up that I really admire—well I just lament they won’t have that same experience. Journalism was a social profession.”

(Visited 75 times, 14 visits today)

[ad_2]

Source_link