[ad_1]

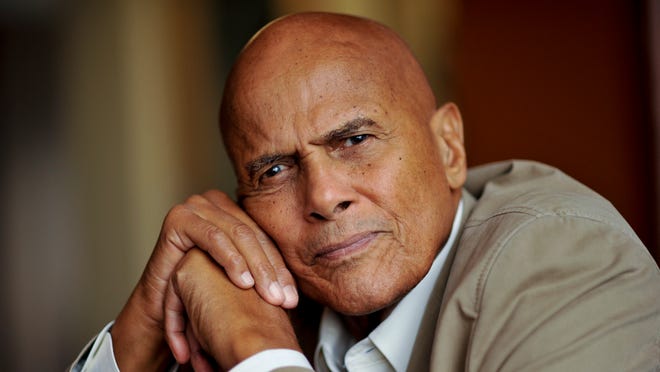

Harry Belafonte, the “King of Calypso” who became one of America’s endearing and enduring civil rights activists into his 10th decade, has died. He was 96.

Belafonte died Tuesday at his home in New York of congestive heart failure, representative Paula Witt said in a statement Tuesday.

Belafonte will be remembered as one of the most popular entertainers of the 20th century, as a singer, musician and actor. But his civil rights work in the 1960s and his anti-apartheid work in the 1980s will be just as enduring.

“I wasn’t an artist who became an activist. I was an activist who became an artist,” Belafonte wrote in his 2011 memoir. “Ever since my mother had drummed it into me, I’d felt the need to fight injustice wherever I saw it, in whatever way I could.”

He did that in a characteristically idiosyncratic fashion, earning admiration for his humanitarian work to relieve hunger and fight cancer, and scorn for his vocal opposition to U.S. foreign policy and his friendship with Cuba’s Fidel Castro. His admiration for his mentor Paul Robeson (the African American concert artist and stage and film actor famous for his civil rights activism and smeared as a communist) also raised eyebrows.

Remembering those we lost: Celebrity Deaths 2023

Belafonte was born Harold George Bellanfanti Jr. in Harlem in 1927, the biracial son of biracial parents, both of whom were born in Jamaica. It made a difference to his musical influences and his later life as a social justice activist that he grew up shuttling between New York and Kingston, Jamaica, still struggling to overcome its colonial past, he said in his 2011 book, “My Song: A Memoir.”

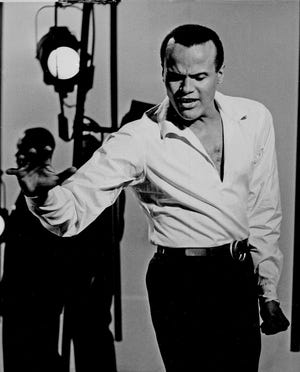

Belafonte burst into the American consciousness thanks to a Jamaican folk song.

Harry Belafonte song ‘Day-O’ (‘The Banana Boat Song’) brought him to fame

No one who heard it in the mid-1950s could ever forget Belafonte’s warm, slightly husky voice on “The Banana Boat Song,” better known as “Day-O” for the opening lyrics of the Jamaican song he recorded in 1956 on his third record, “Calypso.” (Composer Irving Burgie, who co-wrote “Day-O” and eight of the 11 songs on “Calypso,” died Nov. 29 at the age of 95.)

“Day-O” was an instant hit and became Belafonte’s signature song. Suddenly, America was mad for the lilting, rhythmic sound of the Caribbean islands. In virtually every live performance, Belafonte’s audiences would enthusiastically join in the song’s call-and-response melody and refrain.

Even more impressive, “Day-O,” once sung by Jamaican banana workers, helped make “Calypso” the first album to sell more than 1 million copies. Not bad for an entertainer who started out as a club singer in New York to pay for his acting classes.

“I was good as a singer, but I wasn’t the best, and I’d known that from the start,” Belafonte wrote in “My Song.” “I had to rely on my acting. And in the end, I could make a case that I was the greatest actor in the world: I’d convinced everyone I could sing.”

Belafonte’s pop music-turned-folk music career was interrupted by his civil rights activism, but he was still recording as late as 2017 when he released “When Colors Come Together,” an anthology of some earlier recordings produced by his son David who wrote lyrics for an updated version of “Island In The Sun,” featuring Belafonte’s grandchildren Sarafina and Amadeus and a children’s choir.

“Now, let me say this about the songs of the Caribbean – almost all Black music is deeply rooted in metaphor,” he told NPR in a 2011 interview promoting his memoir. “The only way that we could speak to the pain and the anguish of our experiences was often through how we codified our stories in the songs that we sang.

“And when I sing the ‘Banana Boat Song,’ the song is a work song. It’s about men who sweat all day long, and they are underpaid, and they’re begging the tallyman to come and give them an honest count – counting the bananas that I’ve picked, so I can be paid.” But sometimes, they were paid only in rum, as the song’s lyrics describe.

“People sing and delight and dance and love it, (but) they don’t really understand unless they study the song that they’re singing, a work song, that’s a song of rebellion,” Belafonte said.

Harry Belafonte movie career spanned decades

Belafonte’s TV and movie career began in 1953 and stretched into 2018 when he appeared in Spike Lee’s “BlacKkKlansman.” He collected his share of first awards: In 1954, he won a Tony Award as best supporting or featured actor in a musical for “John Murray Anderson’s Almanac,” becoming the first Black man ever to receive a Tony. He was also the first Black man to receive an Emmy Award, with his first solo TV special “Tonight with Belafonte” in 1960.

He won three Grammys in the 1960s and won a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 2000. In 2022, he received an early influence award from the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. He has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame and was awarded a Humanitarian Oscar in 2015. He was named a UNICEF goodwill ambassador in 1987, was a recipient of one of the 1989 Kennedy Center Honors for Performing Arts, and was awarded the National Medal of Arts in 1994.

He even had a “Rat Pack” interlude in Las Vegas, performing, as did Sammy Davis Jr., at hotel casinos such as the Sands and the Dunes, which are no longer in operation.

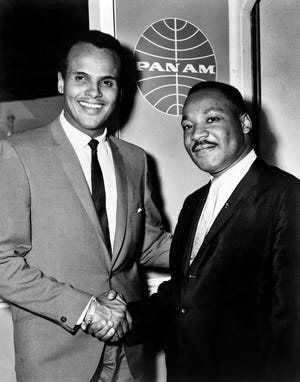

Belafonte’s activism work involved marching with Martin Luther King Jr.

By the 1960s, he was just as famous for being on the front lines of civil rights marches as an early ally of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. By the 1980s, he helped organize the “We Are the World” recording that became the anthem for famine relief in Africa.

He described how he infused his performances with his political passions, performing old favorites and changing up the lyrics to reflect his activism.

“Knowing I was playing to an influential crowd, I’d (sneak) in a little politics with new lines for old songs, like ‘Michael, Row the Boat Ashore’: ‘Mississippi on your knees, Hallelujah!/ Another bus is on the way, Hallelujah,’ ” he wrote in his memoir.

His zeal for social justice was influenced by the nonviolent tactics of India’s Mahatma Gandhi, he said in a 2013 Time issue commemorating the 1963 March on Washington. “We could start this quest for social change by confronting the state a little differently. Let’s do it nonviolently, let’s use passive thinking applied to aggressive ideas, and perhaps we could overthrow the oppression by making it morally unacceptable,” he said.

Belafonte helped organize the game-changing march, which brought more than 250,000 people (including scores of Hollywood stars) to the National Mall and culminated in King’s “I Have a Dream” speech that electrified the civil rights movement.

“In the end, the day was a complete win-win,” Belafonte recounted in the Time magazine article. “…There was not one act of violence. And to see at the end everybody singing ‘We Shall Overcome’ and all the arms linked – we’ve said it often, but it’s worth saying as often as necessary – there wasn’t a dry eye in the house.

“And it was all of America. All of it. You went through that crowd and you couldn’t find any type missing, any gender, any race, any religion. It was America at its most transformative moment.”

Belafonte didn’t back down when it came to his politics.

In October 2002, he made remarks about then-Secretary of State Colin Powell, comparing him to a “house slave.” Powell, a Republican, refused to inflame the situation, merely commenting that Belafonte’s comparison was “unfortunate.” (Powell died Oct. 18, 2021, at the age of 84.)

Nor did he slow down. More than a half-century after the March on Washington, Belafonte was an honorary co-chair of the Women’s March on Washington on Jan. 21, 2017, the day after the inauguration of Donald Trump as president.

To the end, Belafonte wanted to change America and the world.

“I’ve always looked at the world and thought what can I do next? Where do we go from here? How can we fix it? And that’s still how I look at the world because there is so much to be done,” he said in a documentary, “Sing Your Song,” that debuted at Sundance Film Festival in 2011.

“The whole world is caught in human suffering. And those who professed about making change have not come up with answers. We have failed in terms of the moral side. We have to do more.”

[ad_2]

Source_link