[ad_1]

If ever there were a TV drama based on real life that begged to be created, it’s the founding of the Pittsburgh-based Freedom House Ambulance Service in 1967 and its ignoble death eight years later due to racism and the political hackery of the Flaherty administration.

Published last September, Kevin Hazzard’s book, “American Sirens: The Incredible Story of the Black Men Who Became America’s First Paramedics,” tells the Freedom House Ambulance Service story with both narrative style and a sense of historical drama it deserves.

“American Sirens” fills the gaps that WQED’s very impactful 28-minute documentary, “Freedom House Ambulance: The First Responders,” (2023) isn’t able to accomplish with limited archival footage, even though it lacks the vital images that make “The First Responders” such an eloquent document of those times more than half a century ago.

Still, both accounts of the birth and death of America’s first ambulance service staffed by Black citizens trained to save lives are invaluable because they expertly strip away the veil of civic intolerance that made Freedom House Ambulance Service so necessary in a city still clinging to the assumptions of the Jim Crow era.

In the WQED documentary, former Freedom House Ambulance worker Mitchell Brown spells out the reason the emergency service that was located in the Hill District came into existence in the first place: “Back in the Sixties,” Brown says, “you stood a better chance of surviving a gunshot wound in Vietnam than you did a car accident in the city of Pittsburgh.”

Ambulances in one form or another have existed in America since the Civil War when wounded and dying soldiers were ferried to field hospitals by horses dragging their makeshift cots.

In later years, police officers using patrol cars to taxi everyone from gunshot victims to those in the midst of giving birth weren’t expected to alleviate pain and suffering in the field. Their job was to get them to the nearest hospital if there was time or to the morgue if there wasn’t.

Before Freedom House Ambulance Service came into existence, if you were having a stroke or a heart attack, you or someone on your behalf called the police to get you to the hospital.

If you were lucky, the police arrived on time to escort you to the back seat of a police car or the back of a paddy wagon. If you were Black, chances are the cops showed up when it was too late to save your life or not at all.

As Brown says in the WQED documentary, your chances of surviving were better if you were a gunshot victim in Vietnam. That was not an exaggeration.

In those days, a friend or loved one drove you to the nearest emergency room. If you didn’t have access to a vehicle or lacked caring people in your life, then it was up to the police to do the honors. Because the tensions between the police and Black communities were high everywhere, waiting for the police to speed to the rescue was a crapshoot at best.

Saving Black lives was not a high priority for Pittsburgh police in the mid-1960s when Dr. Peter Safar, the inventor of CPR who had a practice at Presbyterian University Hospital, began envisioning the role of paramedics and nontraditional medical practitioners in an urban environment.

Dr. Safar’s proximity to the Hill District, and his ability to see the Black men and women who lived there as valuable human beings endowed with dignity and intelligence, would soon transform emergency critical care in America — and beyond — for the better.

“Dr. Safar wanted to show that people they marked unemployable were really just waiting on opportunity,” says former Freedom House Ambulance Service driver George McCary III in “The First Responders.”

The ranks of that first generation of paramedics trained under the auspices of Dr. Safar in the Hill District included men who had criminal records, were former substance abusers and were considered unsavory characters by the standards of the times.

They were also highly intelligent, civic-minded men capable of learning cutting-edge medical techniques and saving lives under pressure. They were calm, cool and unflappable no matter the emergency.

As Black men, they were always regarded with suspicion by “respectable” white society, but as paramedics they were responsible for raising the life expectancy of Black residents of the Hill District, Oakland and other East End neighborhoods to a level that caused people in other communities to become envious.

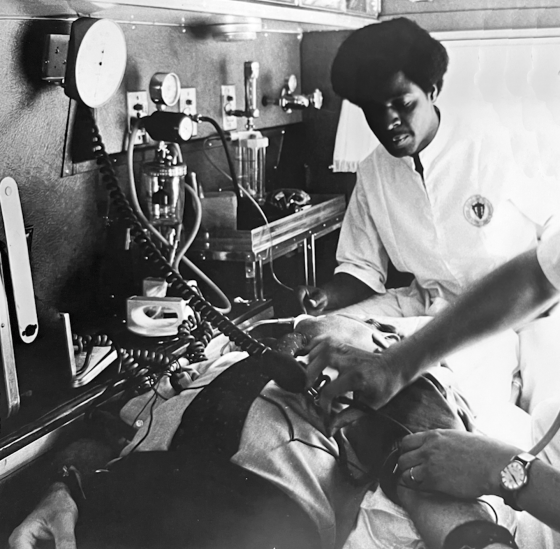

These highly trained Black men were the first emergency workers in the nation to transform an ambulance’s purpose from that of a glorified taxi ride to one where it was in effect an emergency room on wheels. That was a radical paradigm shift in medical services at the time.

Once word got out, white folks began complaining to the politicians on Grant Street that Blacks suddenly had better emergency healthcare outcomes than whites living in more affluent communities.

This was considered politically untenable by the administration of Pittsburgh Mayor Pete Flaherty, who was hostile to Freedom House Ambulance Service because he had no control over it since it was not an initiative of the city.

Freedom House Ambulance Service was initially bankrolled with grants pulled together by philanthropist Philip Hallen of the Falk Foundation, so it was not beholden to the city or the political establishment.

The partnership of Hallen, Safar and the Black paramedics who saved hundreds of lives by speeding to emergencies for nearly a decade, established a template for the nation’s emergency services. It, in turn, was copied around the world. In Pittsburgh, the Flaherty administration took over the ambulance service, hired white paramedics trained by Freedom House’s Black paramedics to run it and pushed out most of those who were there from the beginning.

Last week in a Zoom discussion sponsored by the annual Ravitch Lecture, Hallen and Stanford University professor Dr. Matthew Edwards — a scholar whose specialty is the intersection of race and medicine — talked about the place Freedom House Ambulance Service played in delivering meaningful emergency services to all who needed it and how those initially underestimated and disrespected paramedics changed everything.

It was a riveting discussion that served to remind the several dozen people who were on the Zoom call that amazing things happened in Pittsburgh despite Jim Crow conditions.

The history of Freedom House Ambulance Service proves that good people of all races and communities can’t help but bust out of the limitations placed on them by those who prefer a less healthy, but more segregated reality.

Tony Norman’s column is underwritten by The Pittsburgh Foundation as part of its efforts to support writers and commentators who cover communities of color that historically have been misrepresented or ignored by mainstream journalism.

[ad_2]

Source_link