[ad_1]

By Stuart Mitchner

By Stuart Mitchner

Rachmaninoff is for teenagers. Brahms is for adults!” I overheard this brook-no-dissent proclamation at Princeton’s Cafe Vienna a year before the pandemic shut it down. The speaker was at a nearby table and judging by snatches of conversation coming from his vicinity, he had clout, he knew his stuff, and what he said seemed to make sense at the time.

So began, or begins, this piece on Johannes Brahms, who died on April 3, 1897, 136 years ago Monday, and who was born on May 7, 1833, which makes 2023 his 190th year. I say “began” for “begins” because the first thing I saw yesterday morning when I sat down to breakfast was this headline on the first page of the New York Times’ arts section: “At 150, Rachmaninoff Still Hasn’t Lost His Step.” The opening paragraphs of Joshua Barone’s article mention the composer’s immense popularity, although his reputation has been that of “a sentimentalist and nostalgic who was guilty, worst of all, of being an outlier in classical music’s embrace of modernism.”

So there it is: Rachmaninoff for teenagers, like Classical Music for Dummies. It’s true, one of the few classical records among my mid-teen Basies and Sinatras was Van Cliburn’s best-selling recording of Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 2. A few years later when I was in college and by then in my late teens, a member in good standing of the Columbia Record Club, the only works by Brahms or any other composer I knew were symphonies and concertos. Solo piano pieces, string quartets and such were waiting for the middle-aged father who discovered Franz Schubert in a children’s book shared with his 2-year-old son.

Brahms for Adults

So it goes with selective terminology like “teenagers,” “adults,” “modern,” and “modernism.” One of my favorite books about Brahms and Chopin and other “modern” composers is James Huneker’s Mezzotints in Modern Music, which was published by Scribners two years after Brahms’s death and reprinted multiple times into the 1920s. For Huneker, who died in 1921, “modern” meant music on the brink of the 20th century. I had to look up “mezzotints,” a 17th-century word that according to Merriam-Webster refers to “a manner of engraving on copper or steel by scraping or burnishing a roughened surface to produce light and shade.”

I’ll be quoting Huneker on Brahms because he was one of the most flamboyant and far-seeing writers of his time, who in fact titled his 80-page opening chapter on the composer “The Music of the Future.” His reviews, essays, and stories appeared regularly over a 30-year period in a variety of periodicals both mainstream and avant-garde, including a Manhattan

journal called Town Topics, and were eventually published by Scribners in best-selling collections titled, among others, Melomaniacs, Visionaries, Iconoclasts, and Egoists (A Book of Supermen).

Listening to the Intermezzos

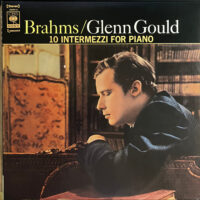

For the past few days I’ve been listening to Brahms/Glenn Gould, a Columbia Masterworks “Anniversary Edition” of 10 Intermezzi and four Ballades. While the musically observant adults at Columbia Records spell the word intermezzi, I prefer intermezzos, which is how it was spelled when I first heard about this unmissable music in emails from a friend in England, who told me he “took refuge in Brahm’s intermezzos. With Brahms you are listening to the creation of beauty.” In an earlier message, he’d termed them “special,” although “a bit unemotional, maybe, and serious, which is odd when you know he started out playing piano in a brothel, a beautiful blond youth who can’t have lacked female attendants.” While various biographers and historians have issues with “the blond youth in the brothel” notion, the 22-year-old Brahms did seem to hint in that direction in a February 12, 1856 letter to his beloved Clara Schumann: “Boys should be allowed to indulge themselves in jolly music, the serious kind comes of its own accord, although the lovesick does not. How lucky is the man who, like Mozart and others, goes to the tavern of an evening and writes some fresh music. For he lives while he is creating.”

Gould’s Choice

I keep asking myself why a pianist as famously daring and provocative as Glenn Gould would choose to record Brahms’s ballads and intermezzos, particularly the Intermezzo in A major, Op. 118, No. 2, one of the composer’s last and most poignant pieces, a twilight-of-life song from the heart where I hope my friend may have found “refuge.” Gould’s thoughtful — you could say loving or even “lovesick” — performance is the last of the set. Why would a musician with a talent for outrage take on music so felt, so tender, so “Silent Night” calm and bright rather than rise to the challenge of the wildly polyphonic Variations on a Theme of Paganini?

I think of Gould in relation to that piece because I sense a Gould-like dynamic in James Huneker’s description of Brahms as the “greatest Variationist,” one “who views his subject from every possible viewpoint; he sees it as a philosopher, he grimly contemplates it as a cynic; he sings it in mellifluous accents, he plays with it, teases it contrapuntally, and alternately freezes it into glittering stalactites and disperses it in warm, violet-colored vapors. The theme is never lost; it lurks behind formidable ambushes of skips, double notes and octaves, or it slaps you in the face, its voice threatening, its size ten times increased by its harmonic garb. It wooes, caresses, sighs, smiles, coquets, and sneers — in a word, a modern magician weaves for you the most delightful stories imaginable, all the while damnably distracting your attention and harrowing your nerves by spinning in the air polyphonic cups, saucers, plates and balls, and never letting them for a moment reach the earth.”

Huneker’s Obsession

One reason Gould might have steered clear of the Variations on a Theme of Paganini, however tempting, is due to its very obviousness as an inducement to sheer virtuosity. And why would Gould want to go head to head with the devil when he could muse on the tender beauties of the intermezzos and ballades? Here’s Huneker on the Variations: “Was ever so strange a couple in harness? Caliban and Ariel, Jove and Puck. The stolid German, the vibratile Italian! Yet fantasy wins, even if brewed in a homely Teutonic kettle. Brahms has taken the little motif — a true fiddle motif — of Paganini, and tossed it ball-wise in the air, and while it spiral spins and bathes in the blue, he cogitates, and his thought is marvellously fine spun.” And Huneker’s off again, spinning and spiraling! He can’t help himself, admitting as much in sentences that might have been taken directly from Balzac: “These diabolical variations, the last word in the technical literature of the piano, are also vast spiritual problems. To play them requires fingers of steel, a heart of burning lava and the courage of a lion. You see, these variations are an obsession with me.”

What you also see is that Huneker is a vicarious musician with intimate knowledge of the piano who has chosen prose for his instrument. And he can play soft and low as in his appreciation of the “purely feminine and questioning” Op. 116 No. 6: “So slender are the outlines of this piece that they seem to wave and weave in the air. The pianissimi are almost too spiritual to translate into tone; and yet throughout, despite the stillness of the music, its rich quiet, there is no hint of the sensuous. The luxuriance of color is purely of the spirit — the spirit that broods over the mystery and beauty of life. Brahms’ music is never sexless; but at times he seems to withdraw from the dust, the flesh-pots and the noise of life, and erects in his heart a temple wherein may be worshipped Beauty.”

So-called modern readers may cringe at that last flourish, where the lush rhetoric of the adult verges on the teenagerly sentimentalism of that old softy Rachmaninoff.

“Sexy, Isn’t It?”

It’s just as well that Gould is heard but not seen in the intermezzos available on YouTube, especially given the playful dialogue between Glenn Gould (GG) and glenn gould (gg) in Michael Stegemann’s CD liner notes (based on Gould’s self-interviews from 1970 and 1974), which begin with GG saying of the performance, “Sexy, isn’t it?” The word “sexy” bothers gg, but after pages of dialogue riffing on numerous controversial statements by GG, it ends where it began with Gould saying, “I find it extremely sexy.”

It’s almost as if by sexing up the liner notes, Columbia is trying to offset Gould’s sensitive performance, which could be called in the most romantic Young Wertherish sense of the word: lovesick. Maybe that’s what makes it sexy. To play against your image. The truth is, Gould manages to keep perfect sympathy with Huneker’s “spirit that broods over the mystery and beauty of life.”

A Living Player

I’ll admit it, ever since my walk by the lake Monday, I’ve been living with the beauty of the Intermezzo in A major, Op. 118, No. 2. During my walk I kept the thread of the song in play, softly whistling the melody that never quite completely happens, that appears and returns, rises and strives and sinks and rises softly and gently again, as it does in the performance by Anna Dmytrenko, a young Ukrainian-American pianist who began her studies at 7 at the Mariupol School of Music in the city razed last year during Putin’s invasion of Ukraine.

Just now I listened to the piece as played by Gould and then the Russian pianist Volodos, who in the liner notes of Volodos Plays Brahms (Sony Music 2017) quotes the 60-year-old composer’s description of the Three Intermezzos Op. 117 “as lullabies for my sorrows.” After Gould and Volodos, I listened to Dmytrenko, with my back to the YouTube image of her live performance. She was more than equal to the beauty of the piece. Then, when the almost-melody comes back again for the last time, I turned around to see her bring it beautifully home. She’s facing the camera, her brow knitted, with no hint of emotional display, nothing but pure concentration, and then when she looks up as the last notes sound, she relaxes into a smile that seems to come from the heart of an old man’s song. I’m reminded of the moment at the Cafe Vienna when I learn that the performance is from 2019, when Anna was 17.

Special thanks, again, to the Princeton Public Library, where I found both CDs.

[ad_2]

Source_link